The following content was complied for a School of Art art history class exhibition. The images are grouped as they were for the exhibit - material types: metals, porcelain, textiles and prints. Contributing researchers, writers, and artists from ARHS 4983 (Spring 2020): JM Barron, Marlene Craig, Yejin Ju, Oh Mee Lee, Alyssa Lor, Tucker Love, Selin Nelson, Mackenzie Patureau, and Alex Tucker.

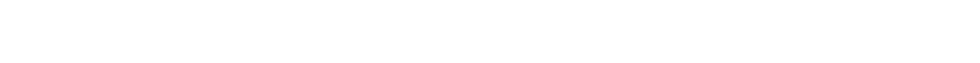

Over thousands of years, cultures in Asia have produced a variety of art forms in bronze, ceramics, textiles, and prints. Bronze production in China reached extraordinary heights during a concentrated time period, c. 1600-256 BCE, and while ceramic and textile production began even earlier, it did not develop in the same way. During the Song dynasty in China (960-1279), textiles and ceramics became the main focus of production, mainly for trade. Subsequently, in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing Dynasties (1644-1912), porcelain bowls and vases were exported around the world. The latest to develop, woodblock prints of urban life were not mass produce in Japan until the Edo period (1603-1868). This exhibition stems from discussions about the level of individual artistic expression versus the perpetuation of cultural representations, and explores the intense specialized processes and particular significance each medium, form, and decoration involved.

Across Asia, workshops of specialized craftspeople worked together to produce porcelains, prints, and silk pieces. Bronze production in China was no different and developed a sophisticated organization of labor much earlier. The bronze jue, or ritual wine vessel, from the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), in this exhibition is one of many produced by a collective of individuals. The jue was one of the most commonly produced forms. Archaeologists have found thousands of bronze vessels in single Shang royal clan members’ tombs. The Incense Burner with Plate from many centuries later, around the 2nd to 3rd century CE, likely comes from a smaller-scale production line, but maintains an accepted form and recognizable motifs. The more recent Incense Burner with Xuande Reign Mark, on the other hand, with its foreign animal motif, suggests a work made specifically for export from China. Like the production of ceramics, textiles, or woodblock prints, to design, mold, and cast a single bronze object required considerable resources and individual numbers of specialists. As a result, these bronze vessels represent one of many, but pass on a wealth of material, cultural, and technological knowledge, individually.

The mass production of works, such as porcelain, left little room for individualized details and artistic expression. The artisan who painted the cobalt blue design on the Spice Jarlet, for instance, clearly used quick imprecise brushstrokes. Other common decorations, such as fish, flowers, phoenixes, and dragons, were also easily copied and reproduced. Practiced artisans simply shaped regular forms, vases and bowls, in an assembly line, ready for decoration and firing. With this well-exercised production and the unproblematic availability of raw materials, porcelain reached high and diverse levels of production, beyond the imperial court, for export and for the common market. This exhibition displays only a small window into this range of production.

Many of the Asian artworks shown here were produced on a large scale, including the ceramics and prints. The mass production of ceramics is typically credited to a workshop or kiln of multiple specialized groups of craftspeople. In the case of Japanese woodblock prints, the master received nearly all of the credit. Printmakers, like Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), worked with studios filled with skilled artisans and laborers to assist with each intricate step required to produce a single print. Due to the complex process of woodblock printing, it was not possible for Kuniyoshi to complete the process alone, however, only his name is passed on. In a similar vein, a number of artists today employ workers to help the produce artworks in their name. In the end, the artist has only a small hand in the making of the final work, ultimately, produced by unknown artisans. With the exception of the Kuniyoshi’s prints, no artworks in this exhibition bear the name of an artist.

While certain works, like the Spice Jarlet and the woodblock prints were mass produced, other works in Joseon Korea (1392-1897) and Ming China were created for specific groups of people, such as those of higher social status. Porcelain was produced in specialized workshops and was often commissioned by those in power or the wealthy. While this method of production left little room for individual inventiveness, specific motifs help us recognize potential patron groups. Through motifs, such as the five-clawed dragon reserved for the emperor, we can identify the specific use of particular vessels. The fine materials and refined craftsmanship often support this categorization. As with the dragon on porcelain, each floral motif and color combination on the hanbok, or traditional Korean dress, can signify social status or special occasion. These forms and motifs have come to reflect a particular culture and, arguably, limited the possibility of individual artistic innovation. A particular porcelain kendi bottle with metal top and phoenix design, or gat, a traditional Korean horsehair hat, both necessitated culturally-protected, traditional techniques, and contain values and symbols that were propagated by their respective forms and production methods. Artistic expression then represents something much greater than an individual’s creation. Later these ideas and aesthetics are reproduced for a broader market, but still, arguably, retain their visual and material ties to their original meaning.

The University of Arkansas Museum Collections acquired the works in this exhibition from named donors. While some of the donors were well-known statesmen or university professors, how each of them obtained these treasures is not completely clear. With questionable origin, the authenticity of the works and their ethical purchase are likewise left uncertain. By studying and exhibiting these diverse materials, we are made aware of their specific value as cultural representations, but at the same time, of how much we cannot know about their individual tested journeys throughout the past four thousand years from various parts of Asia to this trivial and eclectic, but, we hope, meaningful University Museum exhibition.

Photos courtesy of Laurel Lamb, Curator, University of Arkansas Museum.

With many thanks to Laurel Lamb and Dr. Mary Suter of the University of Arkansas Museum, as well as the Department of Art History of the School of Art at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR. In preparation for this exhibition, Professor Bethany Springer (Sculpture), and MFA students Anthony Kascak and Joanna Pike (Ceramics) of the School of Art provided invaluable presentations on bronze and clay processes.